Others, such as the American futurist Ray Kurzweil are much more expansive. Is there something fundamentally different about computer-simulated intelligence?”įrench is among the more pessimistic observers. "No-one would argue that computer-simulated chess playing, regardless of how it is achieved, is not chess playing. “All of this brings us squarely back to the question first posed by Turing at the dawn of the computer age, one that has generated a flood of philosophical and scientific commentary ever since. These issues were summarised by the University of Bourgogne’s Robert M. The video below is illustrative.Īll this raises the question of whether a computer system that finally passes the Turing test is really “conscious” or “human” in any sense. This technology was perhaps brought to the public eye most effectively with the recent defeat of two champion human contestants on the American quiz show Jeopardy! by an IBM-developed computer system known as Watson. Two recent advances have dramatically enhanced interest:ġ) the ready availability of many terabytes of data, from technical documents on every conceivable topic to the growing personal databases of “lifeloggers”Ģ) sophisticated statistical (computational and mathematical) techniques for organising and classifying this data Progress in the field languished somewhat during the 70s and 80s, but since 1991 there has been an annual Loebner Prize in artificial intelligence in which ELIZA’s children - now called “ chat-bots” - compete to pass the Turing test. The present authors do remember enjoying playing with it when personal computers first allowed for relaxed therapy sessions. In 1966, computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created a program, known as ELIZA, which identified keywords in text typed by a human, and then responded with some sort of clever but enquiring response, in the style of a psychologist interviewing a patient.Īlthough some subjects were genuinely surprised to discover the “psychologist” was a computer, to more sceptical testers its weaknesses quickly became evident.

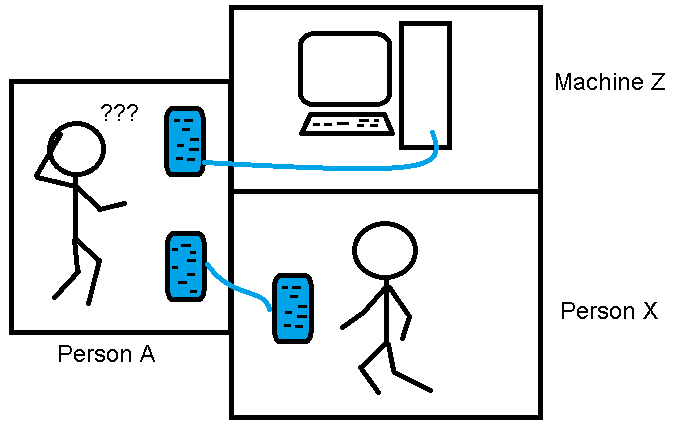

Some early attempts at Turing Test programs pointed out both the promise and the perils of this enterprise. In the decades since 1950, when Turing proposed the test, it has been widely influential in directing progress in the computing field in general and in artificial intelligence in particular. And we all have human acquaintances who might be judged “computer” in such a test. Some potential questions might not be “fair” to a computer. Turing’s article even anticipated several possible objections to his test, including mathematical and philosophical objections, which continue to be debated to the present day. If after, say, five minutes of testing, the majority of human interrogators are unable to determine which is which, Turing said that we could claim the computer system has achieved a certain level of intelligence.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)